Road To Longevity: What You Need To Do

Introduction

Longevity is not just about adding years to life, but adding life to years. As physicians, we recognize that the journey toward healthy aging is built on daily habits, preventive health measures, and timely medical care. Science has revealed much about what influences the length and quality of life—from cellular aging to cardiovascular health, from mental resilience to social connections. The road to longevity is not a mystery; it is a path that requires discipline, knowledge, and conscious choices.

General Readers

For the general reader, the essentials of longevity can be summarized in three pillars: lifestyle, prevention, and balance.

• Lifestyle: Prioritize a balanced diet, rich in whole foods, moderate in calories, and low in processed sugars. Daily physical activity, even brisk walking, sustains cardiovascular and musculoskeletal health.

• Prevention: Regular health screenings for blood pressure, blood sugar, cholesterol, and cancers save lives when done on time.

• Balance: Mental health, sleep hygiene, stress management, and nurturing relationships are equally important. Longevity without peace of mind and purpose loses its meaning.

Medical Students

For medical students, longevity is not only a personal goal but a professional responsibility. Future doctors must understand that aging is a multifactorial biological process. Key points include:

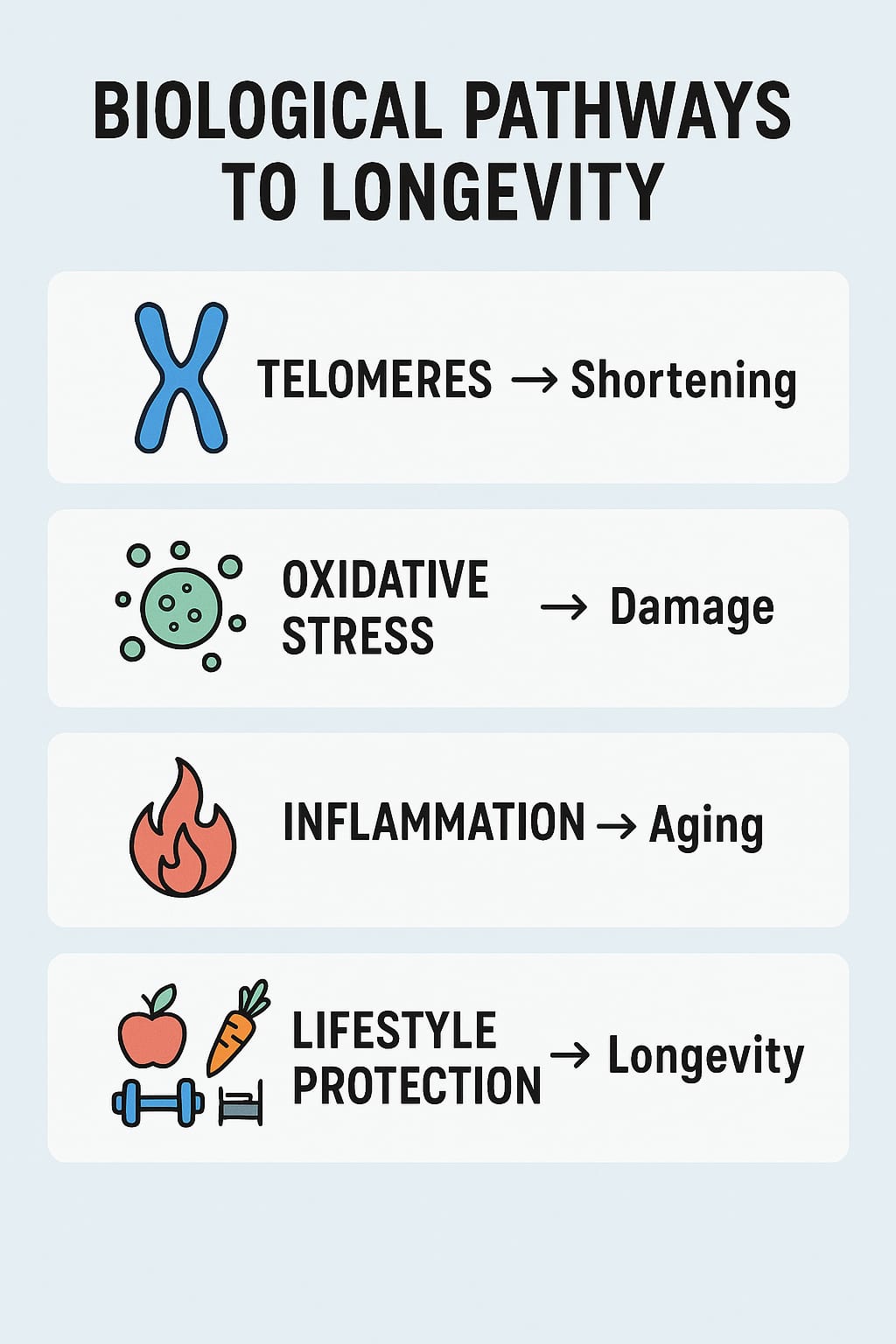

• Molecular Perspective: Oxidative stress, telomere shortening, and chronic inflammation all accelerate aging.

• Clinical Approach: Emphasize primary prevention, vaccination schedules, and patient education as cornerstones of practice.

• Professional Longevity: Your own habits—sleep patterns, coping strategies, and self-care—will determine your endurance in this demanding profession.

Young Doctors

Young doctors often neglect their own health while serving others. The pursuit of longevity must begin early, with conscious protection against burnout and lifestyle diseases.

• Work-Life Balance: Prolonged night duties, poor diet, and lack of exercise often set the stage for hypertension, diabetes, and mental health disorders.

• Role Modeling: Patients look up to doctors. A physician who embodies health inspires confidence.

• Continued Learning: Medicine evolves rapidly. Lifelong intellectual engagement also enhances cognitive longevity.

General Practitioners

For general practitioners (GPs), longevity is not an abstract goal but a daily responsibility toward patients and community health.

• Early Detection: As the first line of healthcare, GPs must identify risk factors for cardiovascular, metabolic, and oncological diseases at the earliest stage.

• Holistic Care: Longevity is not only physical but also emotional, social, and spiritual. Addressing stress, loneliness, and lifestyle choices is as important as prescribing medicines.

• Community Leadership: Encourage vaccination, smoking cessation, and preventive screenings. A single GP can change the longevity profile of an entire population.

When to See the Doctor

Self-care has its limits. The road to longevity requires professional guidance at key intervals. Patients should consult their physician when:

• Routine Screenings: At ages 30, 40, 50, and beyond, structured checkups are essential.

• Warning Signs: Persistent fatigue, unexplained weight loss, chest pain, changes in bowel habits, or prolonged cough must never be ignored.

• Family History: A strong family history of cancer, diabetes, or heart disease necessitates earlier and more frequent medical supervision.

Conclusion

The road to longevity is paved with small but consistent choices—choosing water over soda, a walk over idleness, an early night over late scrolling, and a checkup over neglect. Physicians know that no medicine can substitute for prevention, moderation, and discipline. Whether you are a general reader, a medical student, a young doctor, or a practicing GP, longevity begins with awareness and action today. The ultimate prescription for a long and fulfilling life is simple: live wisely, live consciously, live fully.

Pathophysiology of Longevity

Longevity is a multifactorial outcome determined by the interplay of genetics, cellular mechanisms, metabolic processes, and environmental exposures. Understanding the biological pathways helps explain why some individuals live healthier and longer lives.

1. Cellular Aging and Telomeres

• Every somatic cell has a finite replication capacity, defined by the Hayflick limit.

• With each cell division, telomeres (the protective caps of chromosomes) shorten. Critically short telomeres trigger cellular senescence or apoptosis.

• Accelerated telomere shortening is observed in individuals with chronic stress, smoking, obesity, or uncontrolled inflammation—leading to premature aging.

2. Oxidative Stress and Free Radicals

• Normal metabolism generates reactive oxygen species (ROS).

• Excess ROS damage lipids, proteins, and DNA, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction and impaired cellular repair.

• Antioxidant systems (superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione) decline with age, tipping the balance toward cumulative cellular injury.

3. Chronic Inflammation (“Inflammaging”)

• With age, the immune system undergoes dysregulation, producing low-grade persistent inflammation.

• Elevated cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, CRP) contribute to atherosclerosis, insulin resistance, neurodegeneration, and cancer risk.

• Lifestyle factors like diet, exercise, and sleep can reduce this chronic inflammatory burden.

4. Endocrine and Metabolic Pathways

• Insulin/IGF-1 signaling pathway plays a central role in regulating lifespan. Reduced activity is associated with longevity across species.

• Caloric excess accelerates metabolic stress, obesity, and type 2 diabetes, while caloric moderation supports mitochondrial efficiency and longevity.

• Hormonal decline (growth hormone, sex steroids, melatonin) alters tissue repair, sleep regulation, and metabolism during aging.

5. Cardiovascular and Vascular Aging

• Progressive arterial stiffening (due to elastin breakdown and collagen deposition) increases systolic blood pressure.

• Endothelial dysfunction reduces nitric oxide availability, impairing vasodilation and promoting thrombosis.

• These vascular changes underlie the increased risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, and heart failure in older adults.

6. Neurodegeneration and Cognitive Aging

• Brain aging is characterized by synaptic loss, reduced neurotransmitter activity, and accumulation of misfolded proteins (amyloid, tau).

• Cerebral microvascular disease contributes to dementia and stroke risk.

• Cognitive reserve, maintained through education, intellectual activity, and social engagement, delays clinical manifestation of decline.

7. Genetic and Epigenetic Influence

• Longevity clusters in families, indicating a genetic component. Genes involved include those regulating DNA repair, lipid metabolism, and inflammatory response.

• Epigenetic changes (DNA methylation, histone modification) accumulate with age, altering gene expression and cellular function.

8. Protective Mechanisms of Lifestyle Interventions

• Exercise enhances mitochondrial biogenesis, improves insulin sensitivity, and reduces systemic inflammation.

• Balanced nutrition supplies antioxidants, reduces metabolic stress, and maintains gut microbiota diversity.

• Sleep regulates hormonal cycles (cortisol, melatonin, growth hormone) critical for tissue repair.

• Social connectedness and stress control modulate neuroendocrine pathways (HPA axis), protecting against cardiovascular and psychiatric disease.

Summary

Pathophysiology of longevity rests on the balance between damage accumulation (oxidative stress, inflammation, telomere attrition) and repair mechanisms (DNA repair, autophagy, mitochondrial resilience). Lifestyle and preventive medicine shift this balance toward protection, enabling humans to not only extend lifespan but also maintain healthspan.