Diabetes: The Complete Guide for Patients and Doctors

“If you want a quick summary, please, read our condensed version.”

Chapter 1: Understanding Diabetes

What is Diabetes Mellitus?

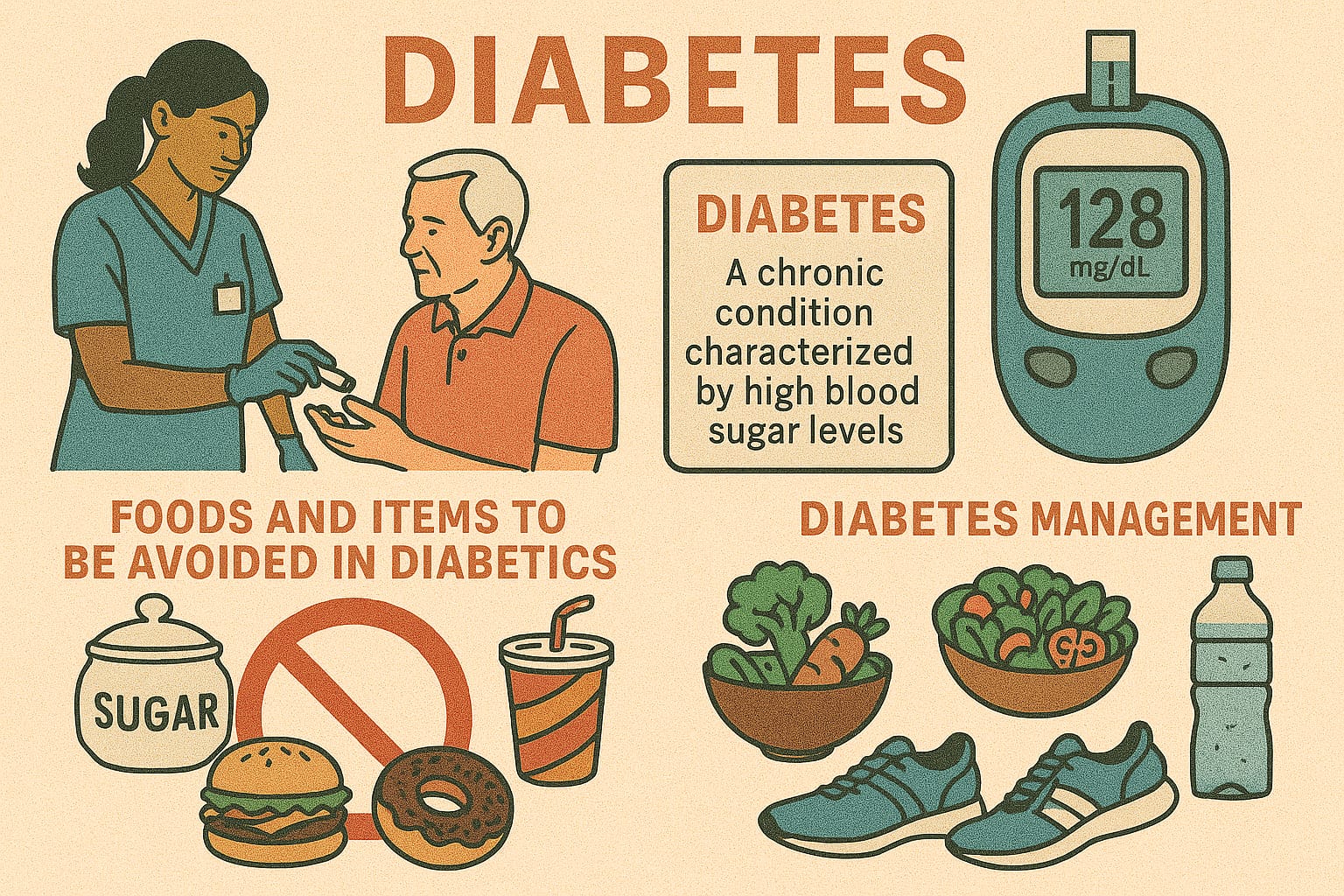

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a chronic metabolic disorder characterized by persistent hyperglycemia — an abnormally high level of glucose in the blood. It results either from:

• Deficient insulin secretion (the pancreas does not make enough insulin),

• Impaired insulin action (cells do not respond properly to insulin),

• Or a combination of both.

Insulin, secreted by the beta cells of the pancreas, is the key hormone responsible for allowing glucose to enter cells and provide energy. Without effective insulin action, glucose accumulates in the bloodstream, damaging multiple organs over time.

Why Diabetes Matters?

• It is one of the leading non-communicable diseases worldwide.

• WHO estimates more than 530 million adults live with diabetes globally, and the number is still rising.

• It contributes significantly to heart disease, kidney failure, blindness, stroke, and limb amputations.

• Beyond health, diabetes imposes a social and economic burden on families and healthcare systems.

Classification of Diabetes

1.3.1 Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus (T1DM)

• Autoimmune destruction of pancreatic beta cells → absolute insulin deficiency.

• Usually presents in children, adolescents, or young adults.

• Sudden onset with symptoms like excessive thirst, frequent urination, weight loss, and fatigue.

• Requires lifelong insulin therapy from the beginning.

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM)

• Accounts for 90–95% of all cases worldwide.

• Caused by insulin resistance (cells fail to respond to insulin) combined with gradual decline in insulin secretion.

• Strongly associated with obesity, sedentary lifestyle, family history, and aging.

• May remain asymptomatic for years and often diagnosed during routine tests.

• Managed initially with lifestyle changes and oral medications; may eventually require insulin.

Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM)

• Develops during pregnancy, typically in the second or third trimester.

• Due to hormonal changes causing insulin resistance.

• Usually resolves after childbirth but significantly increases the mother’s risk of developing Type 2 diabetes later in life.

• Can cause complications for the baby (large birth weight, neonatal hypoglycemia).

1.3.4 Secondary Diabetes

• Occurs as a result of other medical conditions or drugs.

• Examples:

• Endocrine disorders: Cushing’s syndrome, acromegaly, hyperthyroidism.

• Medications: Long-term corticosteroids, thiazide diuretics, some antipsychotics.

• Pancreatic diseases: Chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic surgery, tumors.

Prediabetes: The Silent Stage

Prediabetes is an intermediate stage between normal glucose tolerance and full-blown diabetes.

• Fasting glucose: 100–125 mg/dL

• HbA1c: 5.7–6.4%

• OGTT 2-hour value: 140–199 mg/dL

Why it matters:

• Many patients in this stage progress to diabetes within 5–10 years if untreated.

• Early intervention (diet, exercise, weight reduction) can reverse prediabetes or significantly delay progression.

Summary

Diabetes is not a single disease but a spectrum of disorders ranging from prediabetes to lifelong insulin dependency. Understanding the type, mechanism, and risk profile is the foundation for proper diagnosis and treatment.

Chapter 2: Causes and Risk Factors of Diabetes

Why Causes and Risk Factors Matter

Understanding what causes diabetes and what increases the risk is critical for both prevention and treatment. While some factors such as genetics cannot be modified, many lifestyle and environmental elements can be managed to delay or even prevent diabetes onset—especially Type 2 diabetes.

Causes of Diabetes

Type 1 Diabetes

• Autoimmune destruction: The body’s immune system mistakenly attacks pancreatic β-cells, leading to insulin deficiency.

• Triggers: Viral infections (e.g., Coxsackie virus, mumps, rubella) and environmental factors may initiate the autoimmune process in genetically susceptible individuals.

• Genetic links: HLA-DR3, HLA-DR4, and HLA-DQ alleles are strongly associated.

Type 2 Diabetes

• Insulin resistance: Muscle, fat, and liver cells fail to respond to insulin efficiently.

• β-cell dysfunction: Over time, pancreatic β-cells lose their ability to secrete sufficient insulin.

• Contributors: Obesity (especially abdominal), poor diet, sedentary lifestyle, chronic stress, and aging.

2.2.3 Gestational Diabetes

• Caused by hormonal changes during pregnancy that increase insulin resistance.

• Placental hormones (e.g., human placental lactogen, progesterone, cortisol) play a role.

Secondary Diabetes

• Pancreatic causes: Chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic surgery, cystic fibrosis.

• Endocrine disorders: Cushing’s syndrome (excess cortisol), acromegaly (excess growth hormone), pheochromocytoma (excess catecholamines).

• Medications: Corticosteroids, thiazide diuretics, atypical antipsychotics, immunosuppressants (cyclosporine, tacrolimus).

Non-Modifiable Risk Factors

• Genetics and Family History

• Stronger association with Type 2 diabetes.

• Having a first-degree relative with diabetes significantly raises the risk.

• Age

• Risk increases after 40 years, though Type 2 is now increasingly seen in younger adults and even adolescents due to obesity.

• Ethnicity

• Higher prevalence in South Asians, African Americans, Native Americans, and Hispanics compared to Caucasians.

• Past Medical History

• Women with history of gestational diabetes or polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) are at greater risk.

Modifiable Risk Factors

• Obesity

• Particularly central (abdominal) obesity, strongly linked with insulin resistance.

• Waist circumference is a stronger predictor of diabetes risk than BMI.

• Diet

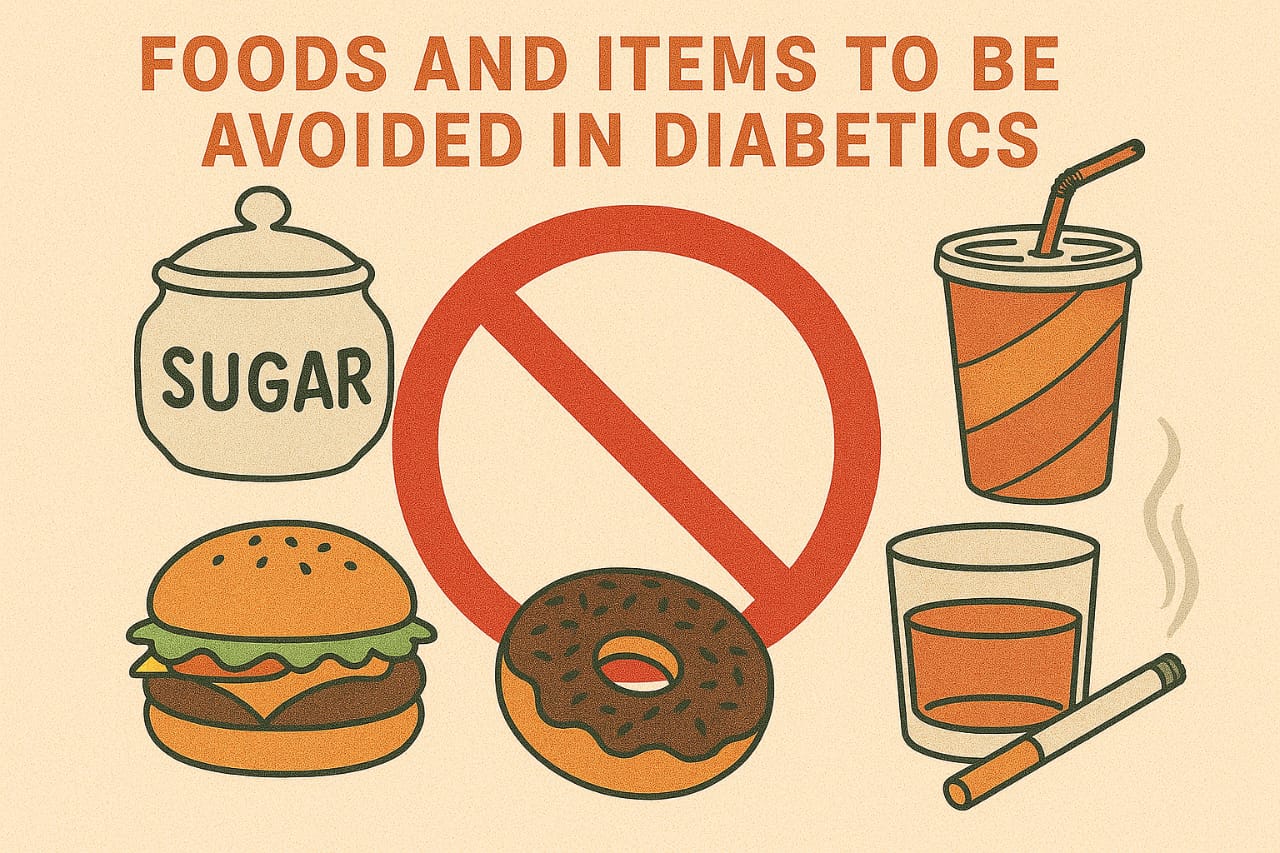

• High intake of refined carbohydrates, sugary drinks, processed foods, and unhealthy fats.

• Low intake of fiber, fruits, and vegetables.

• Physical Inactivity

• Sedentary behavior reduces muscle glucose uptake and increases insulin resistance.

• Smoking and Alcohol

• Smoking increases insulin resistance and risk of cardiovascular complications.

• Heavy alcohol consumption can damage the pancreas and impair glucose control.

• Stress and Sleep Disorders

• Chronic stress raises cortisol, leading to higher blood glucose.

• Poor sleep quality and sleep apnea are linked with insulin resistance.

Risk Factors for Gestational Diabetes

• Maternal age > 25 years.

• Overweight or obesity before pregnancy.

• Family history of diabetes.

• History of GDM in previous pregnancies.

• Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

• Previous large baby (> 4 kg birth weight).

How Risk Factors Interact

• “Two-hit hypothesis” in Type 2 diabetes:

• Hit 1: Genetic predisposition.

• Hit 2: Environmental factors (obesity, diet, sedentary lifestyle).

• When these interact, insulin resistance worsens and β-cells fail → diabetes develops.

Summary

Diabetes develops from a complex interplay of genes, environment, and lifestyle.

• Type 1 is primarily autoimmune, often unavoidable.

• Type 2 is strongly lifestyle-driven and largely preventable with early intervention.

• Gestational and secondary diabetes are triggered by hormonal or external factors.

👉 Identifying modifiable risk factors is the cornerstone of prevention programs, while recognizing non-modifiable risks helps target early screening and monitoring.

Chapter 3: Pathophysiology of Diabetes

Introduction

Pathophysiology explains how and why diabetes develops. While the clinical presentation is “high blood sugar,” the underlying mechanisms differ in each type. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for effective treatment and preventing complications.

Normal Glucose Metabolism

• Insulin secretion: After meals, glucose enters the bloodstream → sensed by pancreatic β-cells → insulin is secreted.

• Insulin action: Insulin allows glucose to enter muscle and fat cells, while suppressing glucose production in the liver.

• Glucagon role: Secreted by pancreatic α-cells, it raises blood glucose during fasting by stimulating liver glucose release.

• Balance: A healthy body maintains fasting glucose around 70–100 mg/dL.

3.3 Pathophysiology of Type 1 Diabetes (T1DM)

• Autoimmune attack: T-lymphocytes destroy β-cells in the pancreas.

• Insulin deficiency: Leads to absolute lack of insulin.

• Result: Glucose cannot enter cells → blood sugar rises (hyperglycemia).

• Ketone production: In the absence of insulin, fat breakdown accelerates, producing ketone bodies → risk of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA).

Pathophysiology of Type 2 Diabetes (T2DM)

Insulin Resistance

• Muscle, liver, and fat cells do not respond well to insulin.

• Glucose uptake is impaired in muscles.

• Liver continues to produce glucose even when not needed.

• Fat tissue releases free fatty acids, worsening insulin resistance.

β-cell Dysfunction

• Initially, the pancreas compensates by producing more insulin (hyperinsulinemia).

• Over time, β-cells “burn out” → insulin secretion declines.

• Combination of resistance + β-cell failure = chronic hyperglycemia.

Inflammation and Genetics

• Obesity triggers release of inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6) → worsen insulin resistance.

• Genetic predisposition determines who will progress from obesity to diabetes.

Pathophysiology of Gestational Diabetes

• During pregnancy, placental hormones (human placental lactogen, progesterone, cortisol, growth hormone) increase insulin resistance.

• Normally, pancreatic β-cells produce more insulin to compensate.

• In women with limited β-cell reserve → glucose rises → gestational diabetes develops.

Pathophysiology of Secondary Diabetes

• Hormonal excess (cortisol, growth hormone, catecholamines) antagonizes insulin.

• Medications (steroids, thiazides, antipsychotics) impair insulin secretion or sensitivity.

• Pancreatic destruction reduces insulin production capacity.

Why High Blood Sugar Causes Damage

• Glycation of proteins (AGEs – Advanced Glycation End-products): Glucose attaches to proteins in blood vessels, nerves, kidneys → structural and functional damage.

Oxidative Stress:

• Excess glucose increases free radicals → endothelial dysfunction.

• Polyol Pathway Activation: In nerves and eyes, glucose converts to sorbitol → causes osmotic and oxidative injury.

• Inflammation: Chronic hyperglycemia promotes low-grade inflammation → accelerates atherosclerosis.

Acute Pathophysiological Events

• Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA):

• Absolute insulin deficiency → uncontrolled lipolysis → ketone body formation → metabolic acidosis.

• Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State (HHS):

• Severe insulin resistance + dehydration → extremely high glucose without ketosis.

Hypoglycemia:

• Due to excess insulin/medication relative to glucose intake.

3.9 Summary

• Type 1: Autoimmune destruction → absolute insulin deficiency.

• Type 2: Insulin resistance + β-cell dysfunction.

• Gestational: Hormonal insulin resistance during pregnancy.

• Secondary: Due to drugs, hormones, or pancreatic damage.

• Long-term hyperglycemia damages tissues through glycation, oxidative stress, and inflammation, leading to complications.

Chapter 4: Symptoms and Early Warning Signs of Diabetes

Introduction

Diabetes may present dramatically, with obvious symptoms, or silently, discovered only on routine tests. Recognizing the early signs is crucial for patients, families, and physicians alike, as early diagnosis can prevent complications.

Classic Symptoms (The “3 Ps”)

• Polyuria (excessive urination)

• High blood sugar spills into urine, dragging water with it → frequent urination, especially at night (nocturia).

• Polydipsia (excessive thirst)

• Fluid loss from urine increases thirst. Patients may drink liters of water daily.

• Polyphagia (excessive hunger)

• Despite high blood sugar, cells are “starving” due to lack of insulin action → increased appetite.

Additional Symptoms

• Unexplained weight loss – common in Type 1, sometimes in uncontrolled Type 2.

• Fatigue and weakness – due to poor energy utilization.

• Blurred vision – glucose changes fluid balance in the eye lens.

• Recurrent infections – urinary tract, skin, fungal infections (Candida).

• Delayed wound healing – due to impaired immunity and poor circulation.

• Tingling or numbness in hands/feet – early neuropathy.

Red-Flag Symptoms (Urgent Attention Needed)

• Nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, fruity breath odor → may indicate diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA).

• Severe dehydration, confusion, very high sugar → possible hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state (HHS).

• Sudden vision loss or severe eye pain → diabetic retinopathy or acute glaucoma.

• Chest pain, stroke-like weakness → macrovascular complications.

Silent or Subtle Presentations

• Many patients with Type 2 diabetes have no symptoms for years.

• Detected incidentally during blood tests for insurance, surgery, or other illnesses.

• Symptoms like mild fatigue or recurrent boils are often overlooked.

• Hence, screening high-risk individuals (obese, family history, hypertension) is vital.

Special Situations

• Children/Adolescents: Bedwetting, irritability, unexplained weight loss.

• Elderly: Often vague symptoms like fatigue, confusion, or recurrent infections.

• Pregnancy: Excessive weight gain, large fetus, recurrent vaginal infections may hint at gestational diabetes.

Summary

The hallmark symptoms of diabetes include polyuria, polydipsia, polyphagia, and weight loss. However, many patients—especially with Type 2—remain asymptomatic for years. High suspicion, early screening, and patient awareness are key to catching the disease before complications set in.

Chapter 5: Diagnosis of Diabetes

Introduction

Diagnosing diabetes is straightforward in most cases but requires precision. Early diagnosis prevents complications, while misdiagnosis can lead to unnecessary treatment. The cornerstone lies in blood glucose measurements and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), supported by history and clinical findings.

Diagnostic Criteria (ADA & WHO Guidelines)

Fasting Plasma Glucose (FPG)

• Normal: < 100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L)

• Prediabetes: 100–125 mg/dL (5.6–6.9 mmol/L)

• Diabetes: ≥ 126 mg/dL (7.0 mmol/L) on two occasions

Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT)

• Performed with 75 g glucose dissolved in water, measuring plasma glucose 2 hours later.

• Normal: < 140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L)

• Prediabetes (Impaired Glucose Tolerance): 140–199 mg/dL (7.8–11.0 mmol/L)

• Diabetes: ≥ 200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L)

Random Plasma Glucose

• Diabetes: ≥ 200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L) with classic symptoms (polyuria, polydipsia, weight loss).

• Useful in emergency/acute presentations.

HbA1c (Glycated Hemoglobin)

• Reflects average glucose over 2–3 months.

• Normal: < 5.7%

• Prediabetes: 5.7–6.4%

• Diabetes: ≥ 6.5% (lab-standardized, repeat for confirmation if asymptomatic).

Advantages: Convenient, no fasting required.

Limitations: May be unreliable in anemia, hemoglobinopathies, recent blood loss, kidney or liver disease.

Additional Tests

• Urine Testing

• Rarely used for diagnosis today.

• May show glucose (glycosuria) or ketones in uncontrolled diabetes.

• C-Peptide Test

• Helps differentiate Type 1 (low/absent C-peptide) vs. Type 2 (normal/high early on).

• Autoantibody Testing

• GAD (glutamic acid decarboxylase) antibodies, ICA (islet cell antibodies) — confirm Type 1 diabetes.

• Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM)

• Increasingly used in Type 1 and complicated Type 2 diabetes for detailed glucose profiles.

Screening Recommendations

• General adult population: Screen every 3 years after age 40.

• High-risk individuals: Overweight/obese, family history, hypertension, dyslipidemia, women with PCOS or GDM history.

• Children/adolescents: If overweight + ≥ 2 risk factors (family history, ethnicity, signs of insulin resistance).

• Pregnancy: Universal screening for GDM between 24–28 weeks.

Pitfalls in Diagnosis

• Stress hyperglycemia: Acute illness (MI, sepsis) can temporarily raise glucose.

• Medications: Corticosteroids, thiazides may elevate glucose.

• Borderline values: Require repeat testing for confirmation.

• Anemia/hemoglobinopathies: May mislead HbA1c interpretation.

Summary

Diagnosis of diabetes rests on plasma glucose and HbA1c criteria.

• FPG ≥ 126 mg/dL, 2-hour OGTT ≥ 200 mg/dL, HbA1c ≥ 6.5%, or random glucose ≥ 200 mg/dL with symptoms are diagnostic.

• Screening high-risk groups is vital since many Type 2 cases are asymptomatic.

• Differentiating Type 1, Type 2, and gestational diabetes at diagnosis guides appropriate therapy.

Chapter 6: Complications of Diabetes

Introduction

The danger of diabetes lies not only in high blood sugar itself but in the short-term emergencies and the long-term complications it causes. Persistent hyperglycemia damages nearly every organ system, leading to disability, reduced quality of life, and premature death if uncontrolled.

Complications are divided into:

• Acute complications – occur suddenly, life-threatening, require urgent treatment.

• Chronic complications – develop over years, progressive, often silent until advanced.

Acute Complications of Diabetes

Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA)

• Most common in Type 1 but may occur in Type 2 under stress.

• Pathophysiology: Lack of insulin → uncontrolled lipolysis → excess ketone production → metabolic acidosis.

• Symptoms: Nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, deep (Kussmaul) breathing, fruity breath odor, dehydration, confusion.

• Emergency: Requires IV fluids, insulin infusion, electrolyte correction.

Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State (HHS)

• More common in Type 2 diabetes.

• Pathophysiology: Severe hyperglycemia (often > 600 mg/dL) without significant ketosis → extreme dehydration and hyperosmolarity.

• Symptoms: Profound dehydration, confusion, seizures, coma.

• Emergency: Managed with aggressive IV fluids, insulin, and electrolyte monitoring.

Hypoglycemia

• Blood sugar < 70 mg/dL.

• Causes: Excess insulin or drugs, missed meals, unplanned exercise, alcohol.

• Symptoms: Sweating, tremors, palpitations, hunger, irritability, confusion, seizures, unconsciousness.

• Management: Immediate glucose (oral if conscious, IV or IM if unconscious).

• Prevention: Patient education and careful drug adjustment.

6.3 Chronic Complications of Diabetes

6.3.1 Microvascular Complications

These result from damage to small blood vessels.

• Diabetic Retinopathy

• Leading cause of blindness worldwide.

• Non-proliferative stage: Microaneurysms, hemorrhages, exudates.

• Proliferative stage: New fragile vessels prone to bleeding, retinal detachment.

• Macular edema → vision loss.

• Prevention: Annual eye exam, good glycemic and BP control, laser therapy if needed.

• Diabetic Nephropathy

• Leading cause of end-stage renal disease.

• Early sign: Microalbuminuria (30–300 mg/day).

• Progression: Proteinuria → declining GFR → renal failure.

• Prevention: Glycemic control, ACE inhibitors/ARBs, BP management.

• Diabetic Neuropathy

• Peripheral: Numbness, tingling, burning pain in feet/hands.

• Autonomic: Gastroparesis, erectile dysfunction, bladder dysfunction, resting tachycardia, orthostatic hypotension.

• Prevention: Glycemic control, foot care, symptom management.

Macrovascular Complications

These result from large blood vessel damage (atherosclerosis).

• Cardiovascular Disease

• Heart attacks (MI) are 2–4 times more common in diabetics.

• Diabetes is considered a coronary artery disease equivalent.

• Cerebrovascular Disease

• Increased risk of stroke, transient ischemic attacks.

• Peripheral Arterial Disease (PAD)

• Narrowing of leg arteries → claudication, poor wound healing, gangrene.

• Often leads to amputations when combined with neuropathy.

Diabetic Foot Complications

• Combination of neuropathy (loss of sensation) and PAD (poor blood flow).

• Results in ulcers, infections, gangrene.

• Prevention: Daily foot inspection, protective footwear, regular podiatry care.

Other Complications

• Skin problems: Fungal infections, boils, diabetic dermopathy.

• Dental issues: Periodontal disease, tooth loss.

• Immune dysfunction: Increased susceptibility to infections (e.g., tuberculosis, pneumonia, urinary tract infections).

Risk Factors for Complications

• Poor glycemic control (high HbA1c).

• Hypertension.

• Dyslipidemia (high LDL, low HDL, high triglycerides).

• Smoking.

• Duration of diabetes (> 10 years greatly increases risk).

Prevention and Early Detection

• Tight glycemic control (HbA1c < 7% for most patients).

• Blood pressure control (< 130/80 mmHg).

• Lipid control (statins as per guidelines).

• Regular screening:

• Eye exam annually.

• Kidney function (urine albumin, eGFR) annually.

• Foot exam at every visit.

• Lifestyle: Diet, exercise, smoking cessation.

Summary

Diabetes complications can be divided into:

• Acute: DKA, HHS, hypoglycemia → life-threatening but reversible with timely treatment.

• Chronic: Microvascular (eyes, kidneys, nerves) and macrovascular (heart, brain, limbs) → progressive, often irreversible, but preventable with strict control.

👉 The burden of diabetes is not just high sugar, but the disability and death caused by complications. Prevention through education, control, and regular screening is the key.

Chapter 7: Management Principles of Diabetes

Introduction

Management of diabetes is not just about lowering blood sugar. It requires a holistic approach targeting:

• Blood glucose control

• Prevention of complications

• Management of comorbidities (hypertension, dyslipidemia, obesity)

• Patient education and empowerment

The goals differ between Type 1, Type 2, gestational, and secondary diabetes, but the guiding principles are similar.

7.2 Lifestyle Modifications (First-Line Therapy)

7.2.1 Nutrition (Medical Nutrition Therapy)

• Balanced meals: Include complex carbohydrates, lean proteins, healthy fats, and fiber.

• Glycemic index (GI): Prefer low-GI foods (whole grains, legumes, non-starchy vegetables).

• Portion control: Essential to prevent calorie overload.

• Limit refined sugars & processed foods: Sweets, bakery items, soft drinks.

• Healthy fats: Olive oil, nuts, fish; avoid trans-fats.

• Meal timing: Consistency helps maintain stable glucose levels.

• Cultural adaptation: Diet must be tailored to local foods (e.g., chapati, lentils, seasonal fruits in Pakistan).

7.2.2 Physical Activity

• At least 150 minutes/week of moderate aerobic exercise (walking, cycling, swimming).

• Add resistance training 2–3 times/week (improves insulin sensitivity).

• Minimize sedentary time (limit screen hours, stand/walk breaks).

Weight Management

• Even 5–10% weight loss improves insulin sensitivity.

• Bariatric surgery may be considered in morbid obesity with uncontrolled diabetes.

Lifestyle Add-ons

• Quit smoking.

• Limit alcohol.

• Manage stress (yoga, mindfulness, breathing exercises).

• Ensure adequate sleep (7–8 hours/night).

Pharmacological Management

Oral Antidiabetic Drugs (OADs)

• Metformin (Biguanide)

• First-line drug for Type 2 diabetes.

• Reduces liver glucose production, improves insulin sensitivity.

• Weight neutral or weight-lowering.

• Contraindicated in advanced kidney disease.

• Sulfonylureas (Gliclazide, Glimepiride, Glibenclamide)

• Stimulate insulin release.

• Risk of hypoglycemia and weight gain.

• DPP-4 Inhibitors (Sitagliptin, Vildagliptin, Linagliptin)

• Increase incretin levels → stimulate insulin, suppress glucagon.

• Weight neutral, low hypoglycemia risk.

• SGLT2 Inhibitors (Empagliflozin, Dapagliflozin, Canagliflozin)

• Increase urinary glucose excretion.

• Benefits: weight loss, lower BP, protect kidneys and heart.

• Risk: genital infections, dehydration.

• Thiazolidinediones (Pioglitazone)

• Improve insulin sensitivity in fat/muscle.

• Side effects: weight gain, edema, heart failure risk.

Injectable Therapy

• Insulin

• Essential in Type 1 (lifelong).

• In Type 2, added when oral drugs fail.

Types:

• Rapid-acting (Lispro, Aspart)

• Short-acting (Regular)

• Intermediate (NPH)

• Long-acting (Glargine, Detemir, Degludec)

• Premixed (70/30, 50/50 combinations)

• Regimens:

• Basal-only (simplest)

• Basal-bolus (closest to physiologic)

• Premixed (convenient, for stable routines)

• Education is key: injection technique, site rotation, insulin storage, hypoglycemia prevention.

• GLP-1 Receptor Agonists (Liraglutide, Dulaglutide, Semaglutide)

• Enhance insulin secretion, suppress appetite, promote weight loss.

• Shown to reduce cardiovascular risk.

Monitoring

• Self-Monitoring of Blood Glucose (SMBG): Finger-prick testing at home.

• Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM): Useful for Type 1, insulin-treated patients.

• HbA1c: Every 3–6 months.

• Target goals (most adults):

• HbA1c < 7%

• Pre-meal glucose: 80–130 mg/dL

• Post-meal glucose: < 180 mg/dL

Special Considerations

• Elderly: Avoid hypoglycemia; less strict targets may be safer.

• Pregnancy: Insulin is preferred; oral drugs are generally avoided.

• Children/Adolescents: Education, psychosocial support, family involvement.

• Ramadan fasting: Requires pre-planning, medication adjustment, and frequent monitoring.

7.6 The Multidisciplinary Approach

• Physician/Endocrinologist: Core management.

• Diabetes Educator: Teaches self-care, SMBG, insulin technique.

• Dietitian: Tailors culturally appropriate meal plans.

• Nurse: Reinforces lifestyle and medication adherence.

• Podiatrist: Foot care to prevent ulcers.

• Ophthalmologist & Nephrologist: Screening and treatment of complications.

Patient Education and Empowerment

• Teach patients to understand their disease.

• Encourage self-monitoring, diet logging, physical activity tracking.

• Support groups and counseling improve adherence.

• Patients should recognize hypoglycemia/hyperglycemia symptoms early.

Summary

Diabetes management is built on three pillars:

• Lifestyle changes (diet, exercise, weight control).

• Medications (oral drugs, insulin, injectables tailored to patient needs).

• Monitoring and education (patient self-management + regular medical supervision).

A team-based, individualized plan achieves the best long-term results, prevents complications, and improves quality of life.

Chapter 8: Monitoring and Follow-Up in Diabetes

Introduction

Diabetes management does not end with prescribing medications. Regular monitoring is the backbone of effective care, ensuring good control, early detection of complications, and timely adjustments in therapy. Both self-monitoring by the patient and professional follow-up by the doctor are essential.

Self-Monitoring of Blood Glucose (SMBG)

Who needs it?

• All Type 1 diabetics

• Type 2 patients on insulin or multiple medications

• Pregnant women with diabetes

• Patients prone to hypoglycemia

Frequency:

• Type 1: 3–6 times/day (before meals, bedtime, sometimes 2 hours post-meal).

• Type 2: At least once daily or several times per week (varies with treatment).

Benefits:

• Helps patients understand the effect of meals, exercise, and medications.

• Guides dose adjustment of insulin.

• Prevents hypoglycemia.

• Limitations: Cost, finger-prick discomfort, compliance issues.

Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM)

• A device with a subcutaneous sensor that records glucose every few minutes.

• Provides 24-hour glucose profile including fluctuations at night and after meals.

Very useful for:

• Type 1 diabetes

• Uncontrolled or brittle diabetes

• Children and adolescents

• Those with frequent hypoglycemia

• Becoming more common with advanced technology and smartphone connectivity.

Laboratory Monitoring

• HbA1c (Glycated Hemoglobin)

• Reflects average glucose of the past 2–3 months.

• Target for most adults: < 7%

• Repeat every 3–6 months depending on control.

Kidney Function

• Urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (for microalbuminuria).

• Serum creatinine and eGFR.

• Frequency: yearly (more often if abnormal).

Lipid Profile

• At diagnosis, then annually.

• Aim: LDL < 100 mg/dL (or < 70 in high-risk patients).

Liver Function Tests (LFTs)

• Baseline and periodically, especially if on statins or pioglitazone.

Thyroid Function

• Particularly in Type 1 (autoimmune association).

Screening for Complications

• Eyes (Retinopathy): Dilated fundus exam at diagnosis (Type 2) or 5 years after (Type 1), then annually.

• Feet (Neuropathy + PAD): Inspection at every visit; monofilament testing annually.

• Heart: ECG at baseline; consider stress testing in high-risk patients.

• Dental: Regular checkups (gum disease more common in diabetes).

Follow-Up Visits

Every 3 months (or more frequently if uncontrolled):

• Review blood sugar records.

• Adjust medications/insulin.

• Check blood pressure, weight, BMI, waist circumference.

• Reinforce diet and exercise.

Every 6–12 months:

• HbA1c

• Lipid profile

• Kidney function

• Eye exam

• Foot exam

• Special situations:

• Pregnancy: much more frequent follow-up.

• Elderly: individualized targets, more focus on hypoglycemia prevention.

Role of the Patient in Monitoring

• Keep a diabetes diary: blood sugar readings, meals, exercise, insulin doses.

• Recognize early signs of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia.

• Adhere to screening appointments.

• Actively participate in treatment decisions with the physician.

Summary

Monitoring and follow-up in diabetes involves:

• Daily: Self-monitoring (SMBG or CGM).

• Quarterly: HbA1c, doctor visits.

• Annually: Eye, kidney, foot, and cardiovascular screenings.

• Always: Patient education and lifestyle reinforcement.

👉 Continuous, structured follow-up is the key difference between a patient who lives complication-free and one who suffers major disability from diabetes.

Chapter 9: Special Situations in Diabetes

Introduction

While most diabetes patients follow standard treatment approaches, certain groups require special considerations. These include children, pregnant women, the elderly, hospitalized patients, and those who fast (e.g., during Ramadan). Each has unique risks and management strategies.

Diabetes in Children and Adolescents

Type 1 Diabetes (Most Common in Children)

• Usually presents with polyuria, polydipsia, weight loss.

• May present as diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) in 20–30% of cases.

• Treatment:

• Insulin therapy from day one.

• Multiple daily injections (basal-bolus) or insulin pumps.

• Education of family and child regarding SMBG, diet, hypoglycemia management.

• Challenges: Growth, puberty (hormonal surges increase insulin resistance), psychosocial issues, peer pressure.

Type 2 Diabetes in Youth

• Increasingly common due to obesity and sedentary lifestyle.

• Often asymptomatic, detected on screening.

• Management:

• Lifestyle modification is crucial.

• Metformin is first-line drug.

• Insulin may be required if uncontrolled.

• Long-term concern: Complications develop earlier due to longer disease duration.

Diabetes in Pregnancy (Gestational & Pre-existing)

Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM)

• Occurs in ~7–10% of pregnancies.

• Risks: Large baby (macrosomia), difficult delivery, neonatal hypoglycemia.

• Management:

• Diet control and exercise first.

• If not controlled, insulin is preferred (oral drugs generally avoided).

• Frequent monitoring of glucose.

Pre-existing Diabetes in Pregnancy

• Women with Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes entering pregnancy.

• Risks: Congenital malformations, miscarriage, maternal complications.

• Management:

• Pre-conception counseling (optimize HbA1c before pregnancy).

• Stop teratogenic drugs (e.g., ACE inhibitors, statins).

• Switch to insulin if on oral agents.

• Close monitoring during pregnancy and delivery.

Diabetes in the Elderly

• Challenges: Multiple comorbidities, polypharmacy, risk of hypoglycemia, cognitive decline, frailty.

• Targets:

• Less strict HbA1c targets (e.g., < 7.5–8% depending on health status).

• Focus on preventing hypoglycemia, maintaining quality of life.

• Treatment approach:

• Simplified regimens (once-daily insulin, minimal drugs).

• Emphasis on diet, safe exercise, fall prevention.

• Monitor for depression, dementia, social isolation.

Diabetes in Hospital and Surgery

• Stress of illness or surgery increases glucose levels (stress hormones).

• Uncontrolled glucose impairs healing and increases infection risk.

• Management:

• Frequent glucose monitoring in hospital.

• Insulin is preferred in acute care (IV insulin in ICU settings).

• Stop metformin if risk of renal impairment or contrast studies.

• Ensure good perioperative glucose control (target 140–180 mg/dL).

Diabetes and Fasting (Ramadan & Religious Fasts)

• Challenges: Long periods without food → risk of hypoglycemia, dehydration, post-iftar hyperglycemia.

• Who should avoid fasting?

• Type 1 patients with poor control.

• Pregnant women with diabetes.

• Patients with recurrent hypoglycemia or advanced complications.

Safe fasting guidelines:

• Pre-Ramadan assessment with doctor.

• Adjust insulin and oral drug timing (e.g., reduce sulfonylurea dose).

• Encourage balanced Suhoor (slow-digesting carbs, protein, fluids).

• Avoid high-sugar foods at Iftar.

• Frequent SMBG even during fast.

• Break fast if glucose < 70 mg/dL or > 300 mg/dL.

Diabetes with Coexisting Conditions

• Hypertension & Dyslipidemia: Treat aggressively to reduce cardiovascular risk.

• Kidney disease: Adjust drug dosages (avoid metformin if GFR < 30).

• Liver disease: Use caution with statins, certain oral drugs.

• Infections: Control sugar tightly to reduce infection severity.

Summary

Special situations require tailored management:

• Children: insulin, family support, psychosocial care.

• Pregnancy: insulin-based control, avoid oral drugs, frequent monitoring.

• Elderly: simplify therapy, prioritize safety.

• Surgery/hospitalization: insulin-based, frequent monitoring.

• Fasting: individualized advice, careful drug adjustment, education.

Individualization is the golden rule — diabetes care is never “one-size-fits-all.”

Chapter 10: Preventing Diabetes

Introduction

While Type 1 diabetes is generally not preventable, Type 2 diabetes — which accounts for the majority of cases worldwide — is largely preventable through lifestyle interventions and early detection. Prevention reduces the burden of disease, avoids complications, and saves healthcare costs.

Preventing Type 1 Diabetes

• Currently, there are no established strategies to prevent Type 1 diabetes.

• Research is ongoing into:

• Immunotherapy (to suppress autoimmune destruction).

• Identifying high-risk individuals through antibody screening.

• Focus is on early detection and avoiding DKA at presentation.

Preventing Type 2 Diabetes

Prediabetes: The Critical Window

• Prediabetes affects hundreds of millions worldwide.

• Without intervention, 5–10% progress to diabetes every year.

• Lifestyle change can reduce risk by up to 58% (proved in landmark studies like the Diabetes Prevention Program).

Lifestyle Interventions

• Weight Control

• Even modest weight loss (5–10% of body weight) improves insulin sensitivity.

• Long-term goal: Maintain healthy BMI (18.5–24.9).

• Dietary Measures

• Reduce refined carbs and sugary drinks.

• Prefer high-fiber foods (whole grains, vegetables, legumes).

• Include lean protein, healthy fats (nuts, olive oil, fish).

• Portion control: Avoid overeating.

• Physical Activity

• Minimum 150 minutes/week of moderate exercise.

• Add resistance training (muscle activity improves insulin uptake).

• Reduce sedentary time (stand/walk breaks at work).

• Behavioral Modifications

• Stress management (yoga, meditation, deep breathing).

• Adequate sleep (7–8 hours).

• Quit smoking, limit alcohol.

Medications for High-Risk Individuals

• Metformin may be considered in:

• Prediabetes with BMI > 35

• Age < 60 with other risk factors

• Women with prior gestational diabetes

• Statins and antihypertensives may be needed to control cardiovascular risk.

Preventing Gestational Diabetes

• Maintain healthy weight before pregnancy.

• Regular exercise and balanced diet during pregnancy.

• Screen high-risk women early (first trimester).

• Universal screening at 24–28 weeks gestation.

Community and Public Health Strategies

• Public awareness campaigns about diet and exercise.

• School-based programs to promote physical activity.

• Urban planning: parks, walking tracks, cycling paths.

• Workplace wellness initiatives.

• National screening programs for high-risk groups.

Summary

• Type 1 diabetes: Prevention not yet possible, but early detection is key.

• Type 2 diabetes: Mostly preventable through lifestyle modification, weight management, exercise, and early use of metformin in high-risk individuals.

• Gestational diabetes: Prevented by healthy maternal lifestyle and early screening.

• Public health efforts are essential to curb the global diabetes epidemic.

The fight against diabetes is not just in clinics but also in homes, schools, workplaces, and communities.

Chapter 11: Doctor’s Corner

Introduction

For doctors, diabetes management goes far beyond writing a prescription. It involves clinical judgment, patient counseling, individualized therapy, and long-term partnership with the patient. This chapter highlights practical strategies for general practitioners, internists, and young doctors.

Approach to a Newly Diagnosed Patient

• Confirm Diagnosis

• Repeat abnormal glucose test if asymptomatic.

• Rule out stress hyperglycemia.

• Identify type (Type 1, Type 2, gestational, secondary).

• Baseline Assessment

• History: Symptoms, family history, comorbidities, lifestyle, medications.

• Examination: BMI, waist circumference, blood pressure, foot exam.

• Baseline labs: HbA1c, fasting glucose, lipids, kidney function, urine albumin, LFTs.

• Patient Education (at first visit)

• Explain the disease nature and lifelong management.

• Stress importance of diet, exercise, monitoring.

• Teach recognition of hypo/hyperglycemia.

Choosing Initial Therapy (Type 2 Diabetes)

• If HbA1c < 7.5%:

• Lifestyle modification + Metformin.

• If HbA1c 7.5–9%:

• Metformin + second oral drug (sulfonylurea, DPP-4i, SGLT2i, or TZD depending on profile).

• If HbA1c > 9% or symptomatic (polyuria, weight loss, very high glucose):

• Start insulin ± metformin.

• Comorbidities matter:

• Heart disease → SGLT2 inhibitor or GLP-1 agonist preferred.

• CKD → SGLT2 inhibitor preferred.

• Obesity → GLP-1 agonist or SGLT2 inhibitor.

Follow-Up Plan for Doctors

• Review SMBG records at each visit.

• Adjust therapy based on glucose trends, not single values.

• Reinforce lifestyle counseling every time.

• Monitor weight, BP, foot exam at every visit.

• Order HbA1c every 3–6 months.

• Annual: Lipids, kidney, eye check, ECG.

Managing Comorbidities

• Hypertension: Target < 130/80 mmHg. Prefer ACE inhibitors/ARBs.

• Dyslipidemia: Most patients > 40 years need statins.

• Aspirin: Consider in high cardiovascular risk.

• Obesity: Encourage diet, physical activity, consider pharmacologic or surgical options.

Avoiding Polypharmacy and Overtreatment

• Use minimum number of drugs to achieve targets.

• Avoid sulfonylureas or insulin overuse in elderly due to hypoglycemia risk.

• In frail or terminally ill, focus on comfort rather than strict targets.

When to Refer to an Endocrinologist

• Uncertain diagnosis (LADA, MODY, atypical features).

• Poor control despite 3–6 months of optimized therapy.

• Frequent/severe hypoglycemia or recurrent DKA.

• Pregnancy with diabetes.

• Advanced complications (nephropathy, retinopathy, neuropathy).

Counseling Tips for Doctors

• Use simple, culturally appropriate language.

• Involve family members for support.

• Address myths and misconceptions (e.g., “insulin is a punishment”).

• Set realistic goals — small successes build patient confidence.

• Encourage patient to ask questions — builds trust.

Summary

The physician’s role in diabetes is to:

• Confirm diagnosis and classify diabetes.

• Assess baseline status and comorbidities.

• Initiate individualized therapy (lifestyle + drugs).

• Monitor regularly and adjust treatment.

• Manage blood pressure, lipids, and complications proactively.

• Refer complex cases appropriately.

The best doctor is not the one who prescribes the most medications, but the one who partners with the patient for lifelong health.

Chapter 12: Living Well with Diabetes

Introduction

Diabetes is not just a medical condition — it is a lifelong journey. With proper care, education, and mindset, patients can lead long, active, and fulfilling lives. This chapter focuses on quality of life, coping strategies, and empowerment.

Coping with a Chronic Disease

• Accept that diabetes is manageable, not curable.

• Focus on what you can control: diet, exercise, medication adherence, stress management.

• Avoid fear and misinformation — diabetes is not the end of life.

Building a Daily Routine

• Regular meals: Consistent timing prevents sugar spikes.

• Exercise habit: Walking after meals, stretching, or sports.

• Sleep hygiene: 7–8 hours, avoid late-night meals.

• Medication adherence: Use reminders, pill boxes, or family support.

• Self-monitoring: Routine glucose checks, diary keeping.

Mental and Emotional Health

• Diabetes distress is real — feelings of burnout, frustration, or guilt.

• Depression is more common in diabetics; screen regularly.

• Counseling, mindfulness, and stress-reduction techniques help.

• Support groups (in person or online) reduce isolation.

Family and Social Support

• Involve family in diet and exercise routines.

• Educate family about recognizing hypoglycemia and emergencies.

• Social activities should not be restricted — adapt food and routine, not life itself.

Success Stories: The Positive Side

• Many patients with diabetes have lived healthy lives for 40–50 years without complications.

• Athletes, actors, leaders with diabetes show that it does not limit achievement.

• Message: With control and discipline, diabetes becomes a “companion,” not a killer.

Practical Tips for Living Well

• Carry a glucose snack (like dates, candy) to treat hypoglycemia.

• Wear a medical ID bracelet if on insulin.

• Don’t hide the condition — share with close friends, workplace, teachers (for children).

• Travel smart: carry medication, insulin, snacks, and prescriptions.

• Celebrate small victories: good HbA1c, weight loss, fewer hypoglycemia episodes.

12.8 Patient Empowerment

• Learn the science of your condition — knowledge reduces fear.

• Take an active role in treatment decisions with your doctor.

• Track your progress with apps, diaries, or wearables.

• Remember: You are not just a patient, you are the main manager of your diabetes.

Summary

Living with diabetes requires a balanced lifestyle, emotional resilience, and continuous education.

• With proper support, patients can achieve their dreams, enjoy social life, and live long.

• Diabetes is best managed not in isolation, but with family, doctors, and community working together.

The goal is not just to control sugar, but to live a happy, healthy, and fulfilling life with diabetes.

Chapter 13: When to See the Doctor

Introduction

Diabetes is a self-managed condition for most of the time, but there are moments when professional medical input is essential. Delaying a doctor’s visit can turn a minor issue into a serious complication. This chapter highlights red-flag situations and routine check-up requirements.

Urgent Situations – Seek Immediate Care

• Very High Blood Sugar (Hyperglycemia)

• Persistent glucose > 300 mg/dL despite medication.

• Symptoms: excessive thirst, frequent urination, weakness, drowsiness.

• Very Low Blood Sugar (Hypoglycemia)

• Severe hypoglycemia (< 54 mg/dL), especially if associated with confusion, seizures, or unconsciousness.

• Recurrent episodes even after dose adjustments.

• Signs of Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA)

• Nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain.

• Deep, rapid breathing (Kussmaul).

• Fruity-smelling breath.

• Usually in Type 1, but can occur in stressed Type 2.

• Signs of Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State (HHS)

• Extreme thirst, dehydration, confusion, coma.

• Very high sugar without ketones.

• Chest Pain or Stroke Symptoms

• Diabetes increases risk of heart attack and stroke.

• Any chest discomfort, shortness of breath, sudden weakness, or slurred speech demands urgent evaluation.

• Severe Infection

• Fever, rapidly spreading skin infections, cellulitis, abscesses, pneumonia, urinary infections.

• Infections worsen sugar control and can progress quickly.

• Sudden Vision Changes

• Sudden blurring, double vision, loss of part of vision field.

• May indicate acute eye emergency (retinal bleed, glaucoma).

Routine Medical Visits

• Newly Diagnosed Patients

• Initial follow-up within 2–4 weeks.

• Stable Patients

• Every 3 months: review glucose logs, check HbA1c, BP, weight, medication adjustment.

• Screening Visits

• Eyes: yearly fundus exam.

• Kidneys: urine microalbumin & creatinine yearly.

• Feet: at every visit + detailed annual exam.

• Lipids: yearly.

• ECG/cardiac risk assessment: baseline and periodically.

Special Groups – More Frequent Visits Needed

• Pregnancy: Weekly to biweekly reviews.

• Children & adolescents: Frequent monitoring, especially during growth spurts or puberty.

• Elderly patients: Monitor closely for hypoglycemia, falls, and drug interactions.

• Patients on insulin: Frequent adjustments needed at initiation.

Patient Self-Check Red Flags

Seek medical advice if you notice:

• Wounds or foot ulcers not healing within 7–10 days.

• Numbness or tingling worsening in hands/feet.

• Recurrent infections (skin, urinary, chest).

• Sudden unexplained weight loss or gain.

• Persistent fatigue or depression affecting quality of life.

Summary

Patients with diabetes must see their doctor:

• Immediately for emergencies like DKA, HHS, severe hypo, chest pain, or severe infections.

• Regularly every 3 months for monitoring and therapy adjustment.

• Annually for eye, kidney, lipid, and foot screening.

• More frequently in pregnancy, childhood, elderly, and insulin therapy initiation.

Rule of thumb: If something feels “different” or “suddenly worse” in a diabetic patient, it is better to consult early than to wait.

Chapter 14: Conclusion

Diabetes as a Global Challenge

Diabetes mellitus is one of the fastest-growing chronic conditions worldwide, affecting people across all ages, cultures, and societies. Its impact extends far beyond blood sugar — it is a disease that touches the heart, kidneys, eyes, nerves, and mind, and creates a heavy social and economic burden.

Yet, despite its seriousness, diabetes is also one of the most manageable chronic diseases with today’s knowledge and resources.

Key Messages for Patients

• Understand your condition: Knowledge reduces fear and builds confidence.

• Adopt a healthy lifestyle: Balanced diet, regular exercise, adequate sleep, and stress control are as important as medicines.

• Take medicines regularly: Skipping doses leads to long-term damage.

• Monitor yourself: Check blood sugar, watch for warning signs, never ignore complications.

• Stay connected: With your doctor, family, and support networks — you are not alone.

Key Messages for Doctors and Healthcare Providers

• Treat the patient, not just the number.

• Individualize therapy — there is no single formula for all.

• Focus on comorbidities (hypertension, dyslipidemia) along with sugar control.

• Prevent complications by early screening and intervention.

• Empower patients with education and counseling — half the treatment is in their own hands.

The Role of Society and Public Health

• Promote healthy food choices and physical activity in schools, workplaces, and communities.

• Raise awareness that diabetes is not a “sugar disease” alone but a major cause of heart, kidney, and eye problems.

• Governments must invest in screening, education, and affordable access to medications and insulin.

A Hopeful Outlook

With proper care, people with diabetes can live long, active, and meaningful lives. Advances in technology (continuous glucose monitoring, insulin pumps, new drug classes) and better lifestyle awareness have dramatically improved outcomes.

Diabetes should not be seen as a limitation but as a call to disciplined living. Patients who embrace the challenge often report not just better health but also a stronger sense of self-control, resilience, and appreciation for life.

Final Words

Diabetes is a journey. It requires partnership: patients, doctors, families, and communities walking together. When managed correctly, it transforms from a life-threatening enemy into a manageable condition — one that teaches balance, awareness, and responsibility.

The ultimate goal is not just to control blood sugar, but to preserve life, prevent suffering, and empower individuals to live fully.