Understanding Diabetes: Beyond Sugar Control

As physicians, we often meet patients who believe diabetes is only about “sugar.” They think of it as a number on a glucometer or a reading in a lab report. While blood sugar is indeed the measurable parameter that defines diabetes, the condition itself is far more complex. Diabetes is not simply a problem of sugar—it is a problem of metabolism, blood vessels, hormones, and the body’s delicate balance of energy.

The Bigger Picture of Diabetes

At its core, diabetes is a disorder of how the body handles glucose, the main source of fuel for every cell. When insulin—a hormone produced by the pancreas—cannot work effectively or is insufficient, glucose accumulates in the blood instead of entering the cells. But elevated glucose is only the beginning. Over years, this imbalance damages the walls of blood vessels, nerves, kidneys, eyes, and the heart. Diabetes is therefore a vascular disease as much as it is a sugar disorder.

Why Sugar Alone is Not Enough

Many patients proudly show “controlled sugar levels” and assume they are safe. While important, sugar control alone does not capture the whole picture. A patient with well-controlled glucose but persistently high blood pressure, cholesterol, or obesity remains at significant risk for complications such as stroke, heart attack, or kidney failure. This is why physicians emphasize a comprehensive approach: not just fasting sugar or HbA1c, but also blood pressure, lipid profile, kidney function, and weight management.

Diabetes and the Silent Damage

The challenge with diabetes is that it often advances silently. A patient may feel well while microscopic damage is accumulating in the retina, kidney filters, or tiny nerves of the feet. By the time symptoms appear—blurred vision, tingling, non-healing wounds—irreversible harm has already been done. This is why regular checkups, even when “feeling fine,” are non-negotiable in diabetes care.

The Role of Lifestyle and Mindset

Managing diabetes is not about medicine alone. Food choices, daily physical activity, weight management, and stress control are equally vital. A simple meal rich in vegetables, lentils, and whole grains; a half-hour walk after dinner; and adequate sleep are as powerful as any prescription. Diabetes thrives in sedentary lifestyles, processed foods, and chronic stress. It retreats in the face of discipline, balance, and awareness.

Moving Forward: A Holistic Approach

As physicians, our message to every patient is clear:

• Control the sugar, but do not stop there.

• Protect the heart, kidneys, eyes, nerves, and brain.

• Think of diabetes not as a number, but as a lifelong companion that demands respect, vigilance, and balance.

Understanding diabetes beyond sugar control is the first step toward preventing its devastating complications. Medicine can prescribe tablets or insulin, but the true victory lies in how patients live their daily lives—with awareness, responsibility, and consistency.

1. For Medical Students

Understanding Diabetes: Beyond Sugar Control

As students of medicine, it is tempting to think of diabetes as a simple disorder of elevated glucose. However, it is important to appreciate that diabetes is a multi-system disease.

At its core, diabetes results from either absolute insulin deficiency (Type 1) or relative insulin resistance with inadequate secretion (Type 2). This leads to persistent hyperglycemia, but the real danger lies in the chronic microvascular and macrovascular complications.

• Microvascular: Retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy.

• Macrovascular: Coronary artery disease, stroke, peripheral vascular disease.

Therefore, in clinical practice, diabetes management involves much more than glucose monitoring. Blood pressure control, lipid management, diet, exercise, and screening for complications are equally important.

For you as future doctors, the key lesson is: treat the patient, not just the sugar. Always look for the silent damage diabetes causes, even in an asymptomatic patient.

2. For Young Doctors / Residents

Understanding Diabetes: Beyond Sugar Control

In your early years of practice, you will meet countless patients who define their diabetes by a single number: their “sugar.” It is your responsibility to guide them beyond this limited view.

Remember that while HbA1c reflects glycemic control, the real goal is to reduce long-term morbidity and mortality. Studies such as UKPDS and DCCT have shown that controlling glucose delays complications, but equally important are blood pressure, lipid control, weight reduction, and smoking cessation.

Practical points for daily practice:

• Do not overlook comorbidities: treat hypertension and dyslipidemia aggressively.

• Screen regularly: urine albumin for nephropathy, fundoscopy for retinopathy, foot exams for neuropathy.

• Reinforce lifestyle modification at every visit. Medication alone cannot achieve targets.

• Educate patients that diabetes is a vascular disease, not just a sugar problem.

As young doctors, your role is not only to prescribe but also to educate, prevent, and anticipate. This mindset will define the quality of care you provide.

3. For General Practitioners

Understanding Diabetes: Beyond Sugar Control

In general practice, diabetes is one of the most common chronic conditions you will manage. Patients often arrive focused on “controlling sugar,” but as their physician, you must broaden their understanding.

Diabetes is a cardiometabolic disease. Controlling sugar reduces microvascular complications, but controlling blood pressure, cholesterol, and lifestyle reduces cardiovascular death—the major killer in diabetes.

Your approach should always be comprehensive:

• Target HbA1c, but also aim for blood pressure <130/80 and LDL reduction.

• Encourage diet modifications relevant to the patient’s culture and food habits.

• Promote regular exercise, even simple walking.

• Schedule periodic checks: eyes, kidneys, nerves, feet, and heart.

Most importantly, communicate clearly. Many patients believe “normal sugar = no problem.” Educating them that diabetes silently damages organs is part of your therapy.

For the general practitioner, success lies not only in prescriptions but in continuity of care, patient trust, and prevention of complications.

When we talk about normal ranges in diabetes, we usually focus on a few key lab values and clinical measurements:

Blood Glucose Levels

• Fasting Plasma Glucose (FPG):

• Normal: <100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L)

• Prediabetes: 100–125 mg/dL (5.6–6.9 mmol/L)

• Diabetes: ≥126 mg/dL (7.0 mmol/L) (on two occasions)

• 2-Hour Post-Prandial Glucose (after 75g OGTT):

• Normal: <140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L)

• Prediabetes (Impaired Glucose Tolerance): 140–199 mg/dL (7.8–11.0 mmol/L)

• Diabetes: ≥200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L)

• Random Blood Glucose (with symptoms):

• Diabetes: ≥200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L)

HbA1c (Glycated Hemoglobin)

• Normal: <5.7%

• Prediabetes: 5.7–6.4%

• Diabetes: ≥6.5%

(In established diabetics, the treatment target is often <7%, but can be individualized depending on age, comorbidities, and risk of hypoglycemia.)

Other Key Parameters for Diabetes Management

Because diabetes is more than sugar:

• Blood Pressure: <130/80 mmHg (ideal for diabetics)

• LDL Cholesterol: <70 mg/dL (for high-risk patients), otherwise <100 mg/dL

• Triglycerides: <150 mg/dL

• HDL Cholesterol: >40 mg/dL (men), >50 mg/dL (women)

In summary:

• Fasting <100, 2-hr <140, HbA1c <5.7% = normal.

• Values between normal and diabetes = prediabetes (warning zone).

• Above these thresholds = diabetes diagnosis.

How to monitor treatment ?

Normal Range Monitoring treatment in diabetes goes well beyond checking random sugar readings. As a physician, here’s how we structure it comprehensively:

1. Glycemic Monitoring

• Self-Monitoring of Blood Glucose (SMBG):

• Fasting, pre-meal, post-meal, and bedtime readings when needed.

• Helps assess day-to-day variability and hypoglycemia risk.

• Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM):

• Increasingly used for detailed trends and “time in range.”

• HbA1c (every 3–6 months):

• Reflects average control over 8–12 weeks.

• Goal: usually <7%, but individualized (tighter in young patients, relaxed in elderly/comorbid).

2. Clinical Monitoring

• Symptoms:

• Watch for polyuria, polydipsia, fatigue, blurred vision.

• Equally important: ask about hypoglycemia episodes.

• Weight & BMI:

• Track at every visit; weight gain may reflect over-treatment or poor lifestyle balance.

• Blood Pressure:

• At every visit; target <130/80 mmHg in most patients.

3. Laboratory Monitoring

• Lipid Profile: Annually (LDL, HDL, triglycerides).

• Kidney Function:

• Serum creatinine, eGFR annually.

• Urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio yearly (to detect early nephropathy).

• Liver Function: If on statins or other hepatotoxic drugs.

4. Complication Screening

• Eyes: Annual fundoscopy/retinal photography.

• Feet: Regular inspection for neuropathy, ulcers, infections.

• Neuropathy: Monofilament and vibration sense yearly.

• Cardiac Risk: ECG baseline, stress testing if symptomatic or high-risk.

5. Lifestyle & Adherence Monitoring

• Review diet, physical activity, and stress levels at every visit.

• Assess medication adherence (missed doses, side effects).

• Involve family in education and support.

In summary: Monitoring diabetes treatment means integrated follow-up—sugar control (SMBG, HbA1c), blood pressure, cholesterol, kidneys, eyes, nerves, and heart. It is not enough to see “sugar is normal”—the whole body must be protected.

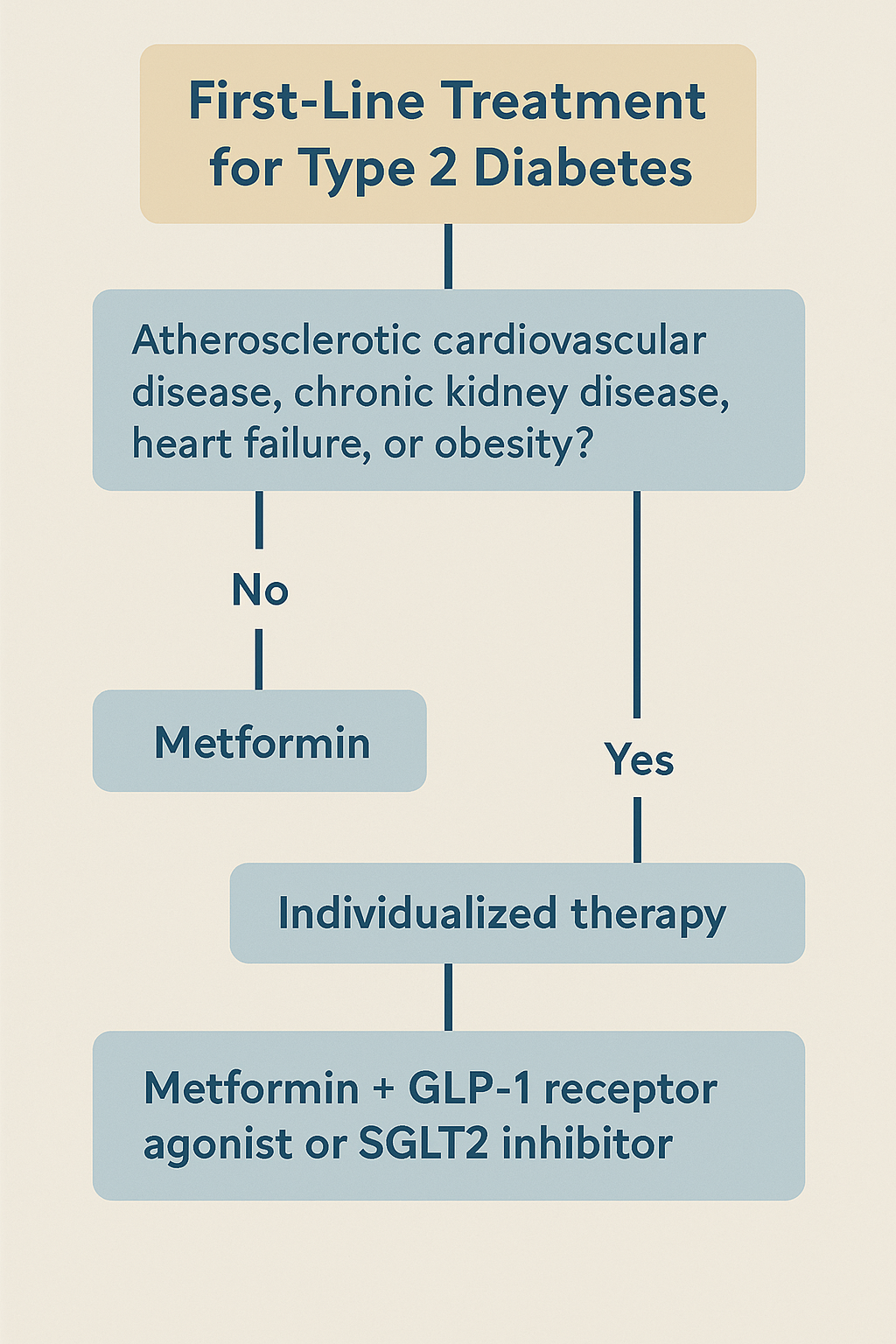

First-Line Drug of Choice: The Current Paradigm

1. Metformin—Still the Bedrock

• Widely endorsed as the initial pharmacologic therapy for type 2 diabetes due to its safety, affordability, and effectiveness. It improves insulin sensitivity, lowers hepatic glucose output, and has a favorable weight and hypoglycemia profile. This remains standard in most guidelines.

(Wikipedia)

2. Emerging Shift: Individualized, Risk-Based First-Line Options

• Across major guidelines, the paradigm is evolving toward a more patient-centered approach. Clinicians are encouraged to consider cardiovascular, renal, and obesity-related benefits when selecting first-line therapy—not just glycemic control.

(Pharmacy Times)

• GLP‑1 Receptor Agonists (GLP‑1 RAs)

• Now considered first-line alongside metformin for patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, obesity, or both—given their demonstrated cardiovascular and weight loss benefits.

• SGLT‑2 Inhibitors

• Similarly recommended as a first-line option (often in combination with metformin) in individuals with chronic kidney disease, heart failure, or high cardiovascular risk, due to their proven cardio-renal protective effects.

(Wikipedia)

Bottom Line

• Metformin remains the default first-line agent for most patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes.

• However, current (2025) best practice emphasizes tailoring initial therapy based on individual comorbidity profiles:

• Use GLP-1 RAs as first-line (with or instead of metformin) in cases of obesity or established atherosclerotic disease.

• Use SGLT-2 inhibitors as first-line (often alongside metformin) in patients with kidney disease, heart failure, or high cardiovascular risk.

Final Guidelines for Type 2 Diabetic Patients:

Here’s a comprehensive overview of the 2025 ADA Standards of Care for Type 2 Diabetes (T2D)—highlighting the most up-to-date, evidence-based recommendations for clinicians as of August 2025:

Summary of the 2025 ADA Standards of Care for Type 2 Diabetes

1. Pharmacologic Treatment: Tailored and Protective

• Metformin remains the foundational first-line therapy for most patients with T2D, chosen for its efficacy, safety, affordability, and favorable metabolic profile. (American Diabetes Association)

• Guidelines increasingly emphasize individualized, combination-first approaches—especially in those with comorbidities:

• GLP‑1 Receptor Agonists (GLP‑1 RAs): Advised not just for glycemic control but also for cardiovascular, renal, and hepatic protection, including in those with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) or MASLD. (American Diabetes Association)

• SGLT‑2 Inhibitors: Recommended for patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) or heart failure, owing to their demonstrated cardiorenal benefits. (Exploration Publishing)

• Dual GIP/GLP‑1 Agonists: Newly incorporated as effective combination agents for both glycemic control and obesity management. (Exploration Publishing)

• Resmetirom (thyroid hormone receptor‑β agonist): Now indicated for moderate to advanced MASLD in T2D. (Exploration Publishing)

2. Technology and Monitoring

• Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM): For the first time, the ADA recommends CGM use even in T2D patients not on insulin, to support behavioral insights and improved glycemic outcomes. (American Diabetes Association)

• Emphasis on CGM-supported education and management—not just insulin titration. (wafp.org)

3. Weight Management & Nutrition

• Updated guidance reinforces lifestyle intervention (diet, physical activity, behavior therapy) as first-line for weight loss, aiming for 3–7% body weight reduction, up to 15% in support of possible remission. (wafp.org)

• For patients on pharmacotherapy for weight loss—continuation is advised even after weight goals are met, due to risk of metabolic relapse. (wafp.org)

• Nutritional strategy: Favor whole foods—fruits, vegetables, legumes, whole grains. Prioritize water over sweetened drinks; use non-nutritive sweeteners only short-term, in moderation. (American Diabetes Association)

• Resistance training (2–3 sessions weekly) is now strongly recommended to preserve muscle during weight loss and improve insulin sensitivity. (diaTribe)

4. Psychosocial and Behavioral Support

• Routine annual screening for diabetes distress, anxiety, depression, fear of hypoglycemia, and disordered eating is now mandated. (wafp.org)

• Diabetes Self-Management Education and Support (DSMES): Encouraged to be personalized, culturally relevant, and accessible, with emphasis on social determinants of health. (Exploration Publishing)

5. Additional Clinical & Context-Specific Guidance

• DKA / HHS Prevention: New tools help stratify outpatient risk; added guidance for diagnosing and managing. (wafp.org)

• Medication Shortages: ADA includes plans for managing interruptions in medication supply. (American Diabetes Association)

• Religious Fasting: The ADA now includes risk assessment tools and adjustment recommendations for diabetes management during fasting periods (e.g., Ramadan).

• The 2025 ADA Standards of Care represent a more holistic, individualized, and technology-supported paradigm for T2D management.

• While Metformin and lifestyle therapy remain foundational, GLP-1 RAs, SGLT-2 inhibitors, and emerging agents like dual agonists and resmetirom offer important organ-specific protection and metabolic benefits.

• Equally central are tools like CGM, psychosocial screening, and tailored DSMES, which enhance engagement and long-term outcomes across diverse patient populations.

By Dr. Mohammed Tanweer Khan

A Proactive/Holistic Physician

Founder of WithinTheBody.com