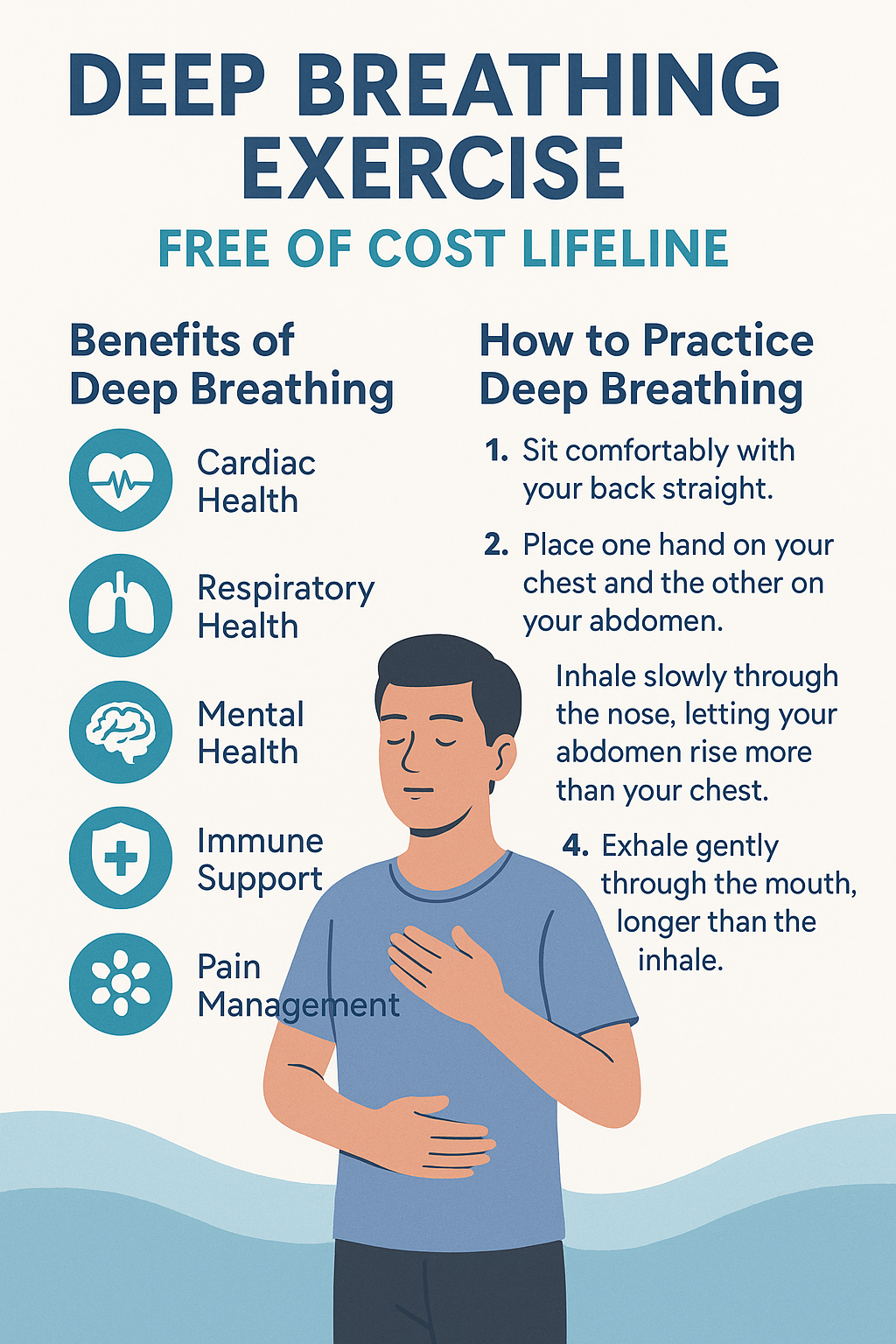

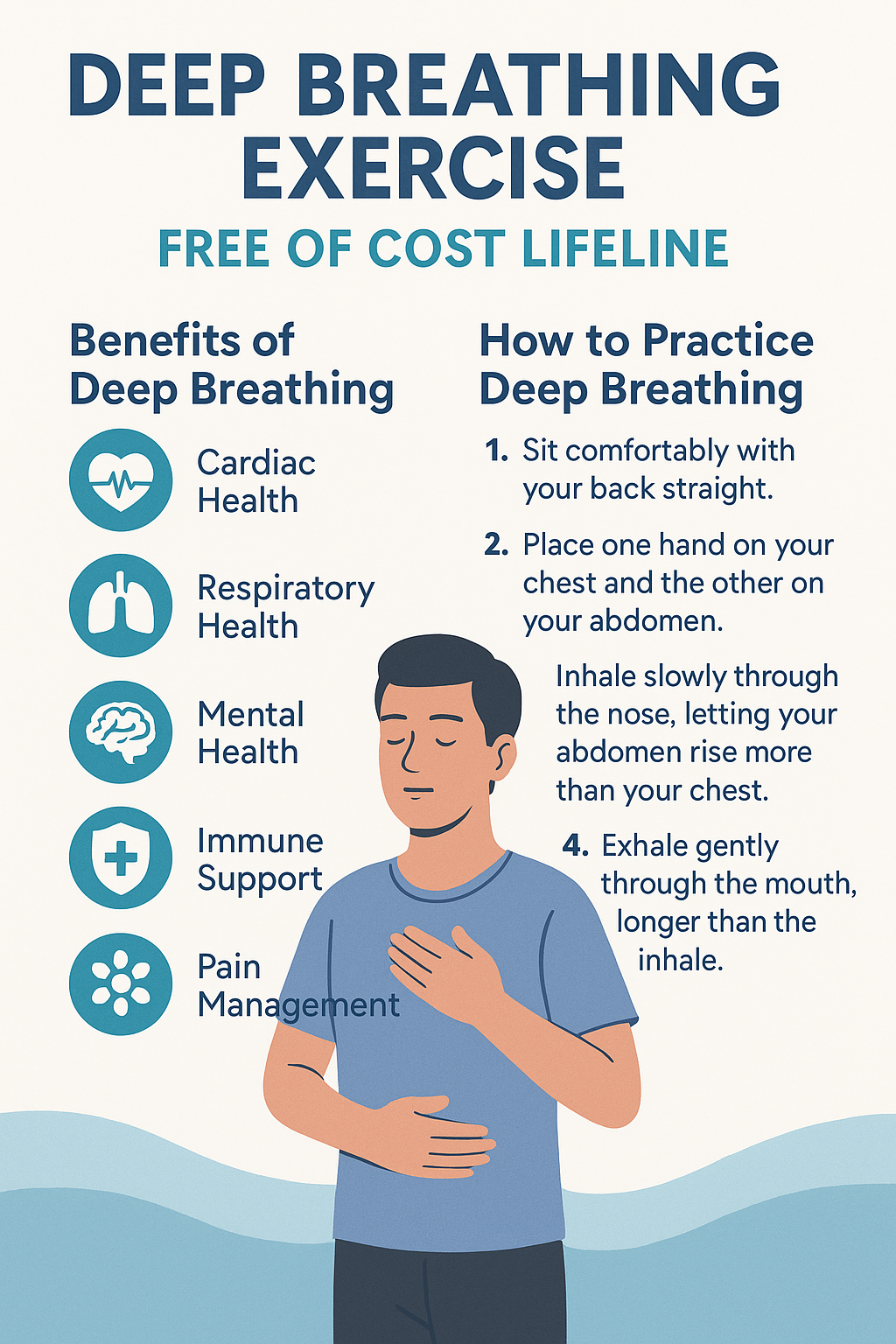

Deep Breathing Exercise: Free of Cost Lifeline

A special article written by Dr. MTK for his website audience. An exclusive article, only found at withinthebody.com

As physicians, we often emphasize medications, investigations, and procedures to manage diseases. Yet, one of the most powerful tools for restoring balance, preventing illness, and even saving lives comes not from a pharmacy or an operating room—but from within our own body. That tool is deep breathing.

What Happens When We Breathe Deeply?

Deep breathing is more than just filling the lungs with air. It is a physiological reset button. When we take slow, deliberate breaths, we activate the parasympathetic nervous system, the body’s natural brake pedal, which reduces heart rate, lowers blood pressure, improves oxygen delivery, and calms the mind.

A single deep breath increases alveolar ventilation, improves oxygen exchange, and enhances blood circulation to vital organs. Repeated over a few minutes, it counteracts stress hormones like adrenaline and cortisol, shifting the body toward healing and restoration.

Medical Benefits of Deep Breathing

• Cardiac Health:

Regular practice reduces heart rate variability, improves circulation, and lowers the risk of hypertension. It acts as a natural adjunct to antihypertensive therapy.

• Respiratory Health:

Deep breathing expands the lungs, prevents atelectasis (collapse of alveoli), and improves lung compliance. For patients with asthma or COPD, it helps in better ventilation.

• Mental Health:

Controlled breathing reduces anxiety, improves concentration, and helps in depression management. Medical research shows significant improvement in stress scores with simple breathing practices.

• Immune Support:

By lowering stress and improving oxygenation, deep breathing enhances immune system performance, helping the body fight infections more effectively.

• Pain Management:

Deep breathing stimulates the release of endorphins, the body’s natural painkillers. Many chronic pain patients find relief with this simple, cost-free method.

How to Practice Proper Deep Breathing

• Sit comfortably with your back straight.

• Place one hand on your chest and the other on your abdomen.

• Inhale slowly through the nose, ensuring your abdomen rises more than your chest.

• Hold for 2–3 seconds.

• Exhale gently through the mouth, longer than the inhale.

• Repeat for 5–10 minutes, two to three times daily.

This technique, called diaphragmatic breathing, ensures maximum oxygen exchange and parasympathetic activation.

Why I Call It a Lifeline

When a patient in the emergency department hyperventilates with anxiety, guiding them to slow, deep breaths stabilizes them without any drug. When a hypertensive patient is anxious about their rising blood pressure, teaching them to practice breathing can drop readings significantly. When a patient struggles with panic, nothing works faster than their own breath.

Unlike medicines, deep breathing has no side effects, no costs, and no barriers to access. It is available to everyone, everywhere, at all times.

Final Word as a Physician

Deep breathing is not just a relaxation technique; it is preventive medicine, adjunctive therapy, and in critical moments, even a lifesaving measure. I urge every patient and every healthy individual alike—practice deep breathing daily. You don’t need an appointment, a prescription, or money. All you need is a few minutes and the willingness to breathe consciously.

It truly is a free of cost lifeline—one that no one should ignore.

Every person—young or old, healthy or ill—can benefit from deep breathing. It lowers blood pressure, reduces stress, improves lung function, strengthens immunity, and calms the mind within minutes.

No medicines.

No machines.

No cost.

Just your own breath, consciously controlled.

By practicing and teaching this to family, friends, patients, and colleagues, you can prevent panic attacks, reduce complications in heart and lung patients, and even help in emergencies like anxiety-induced breathlessness.

➡ Take 5 minutes every day.

➡ Teach at least one person daily.

1. For Medical Students

Deep Breathing Exercise: Free of Cost Lifeline

As future physicians, it is vital to understand that not every therapeutic intervention requires a prescription pad. Deep breathing is one of the simplest yet most effective physiological exercises, and it should not be underestimated.

Mechanism:

Deep breathing stimulates the parasympathetic nervous system via the vagus nerve. This reduces heart rate, lowers blood pressure, and shifts the body from a “fight or flight” to a “rest and digest” state. It also improves alveolar ventilation and gas exchange, thereby enhancing oxygen delivery to tissues.

Clinical Relevance:

• Cardiac: Helps in hypertension and reduces sympathetic overdrive.

• Respiratory: Prevents atelectasis, improves lung compliance, and supports patients with asthma/COPD.

• Neurological/Psychiatric: Lowers cortisol and adrenaline, improving anxiety, concentration, and sleep.

• Immunology: Reduced stress hormones correlate with improved immune function.

Technique:

• Sit upright, place one hand on the chest and one on the abdomen.

• Inhale through the nose, expanding the diaphragm.

• Hold for 2–3 seconds.

• Exhale slowly through the mouth, longer than the inhalation.

Note for Students:

Remember: Deep breathing is preventive, supportive, and therapeutic. It is a practical example of how understanding physiology can guide patients without cost or side effects.

2. For Young Doctors

Deep Breathing Exercise: Free of Cost Lifeline

In your early practice, you will meet patients with hypertension, anxiety, asthma, panic attacks, and even post-surgical complications. While pharmacological therapy is essential, you must also recognize the power of non-pharmacological interventions—and deep breathing is one of the most valuable among them.

Physiological Basis:

Deep breathing activates vagal tone, lowers sympathetic overactivity, improves gas exchange, and stabilizes cardiovascular function. This is a practical and evidence-based way to complement medical treatment.

Practical Applications in Clinics and Wards:

• Hypertensive patient: Guide them through breathing exercises; often blood pressure falls significantly.

• Panic attack: Teach immediate slow breathing to control hyperventilation.

• Post-operative care: Prevents atelectasis and improves recovery.

• Chronic illness management: Enhances compliance and gives patients a sense of control.

How to Counsel Patients:

• Demonstrate the technique yourself (diaphragmatic breathing).

• Advise 5–10 minutes, two or three times daily.

• Reinforce its role as an adjunct, not a substitute, to prescribed medications.

Key Message:

As a young doctor, your clinical strength lies not only in prescribing but also in empowering patients with safe, cost-free methods that significantly improve outcomes. Deep breathing is a prime example.

3. For General Practitioners

Deep Breathing Exercise: Free of Cost Lifeline

In family practice and general medicine, we encounter a wide range of cases—hypertension, diabetes, anxiety disorders, respiratory diseases, and chronic pain. Medications are necessary, but patients often look for holistic solutions. Deep breathing is a simple, cost-free, and highly effective practice you can integrate into daily consultations.

Why Recommend It?

• Cardiac Care: Reduces sympathetic load, lowers BP, and improves heart rate variability.

• Respiratory Health: Enhances lung expansion, prevents atelectasis, useful in asthma/COPD.

• Mental Wellbeing: Calms anxiety, improves sleep, helps in depression management.

• Immune Support: Stress reduction leads to better immunity.

• Pain Relief: Endorphin release provides natural analgesia.

Counseling Strategy for GPs:

• Prescribe deep breathing as you would a medication: “Do this exercise for 5–10 minutes, twice a day.”

• Encourage patients to practice during stress, before sleep, or even while waiting in your clinic.

• Use it as part of preventive medicine, especially for high-risk groups (hypertension, metabolic syndrome, anxiety-prone patients).

Conclusion:

For the general practitioner, deep breathing is more than relaxation—it is a therapeutic tool that improves patient outcomes, reduces drug dependency, and strengthens doctor–patient trust.

What Breathing Actually Is

Breathing (also called ventilation) is the process of moving air into and out of the lungs. It is the first step in respiration, which is the overall exchange of gases between the body and the environment.

Breathing ensures that oxygen (O₂) enters the body and carbon dioxide (CO₂), a metabolic waste product, is expelled. Without it, tissues cannot receive the oxygen required for energy production (ATP synthesis).

The Mechanism of Breathing

Breathing occurs through a coordinated action of the respiratory muscles, lungs, and brain control centers.

1. Inspiration (Inhalation)

• Muscles involved:

• Diaphragm contracts and moves downward.

• External intercostal muscles contract, pulling the ribs upward and outward.

• Effect:

• This increases the size of the thoracic cavity.

• As the volume increases, the intrapulmonary pressure falls below atmospheric pressure.

• Air rushes into the lungs to equalize the pressure.

2. Expiration (Exhalation)

• Normal breathing (quiet expiration):

• The diaphragm and intercostals simply relax.

• Thoracic volume decreases, lung pressure rises above atmospheric pressure.

• Air is pushed out.

• Forceful expiration (like coughing/exercise):

• Internal intercostal muscles and abdominal muscles contract to push air out more strongly.

Control of Breathing

Breathing is both automatic and voluntary.

• Brainstem (medulla & pons): Houses the respiratory centers that automatically regulate breathing rate and rhythm.

• Chemoreceptors (carotid bodies, aortic bodies, medulla): Detect CO₂, O₂, and pH levels and adjust breathing accordingly.

• Voluntary control: The cerebral cortex allows us to consciously hold breath, speak, sing, or practice deep breathing.

Gas Exchange Mechanism

• Air reaches the alveoli (tiny sacs in the lungs).

• Oxygen diffuses from alveoli → blood (into pulmonary capillaries).

• Carbon dioxide diffuses from blood → alveoli to be exhaled.

• This occurs by simple diffusion, driven by partial pressure differences (high O₂ in alveoli → low O₂ in blood; high CO₂ in blood → low CO₂ in alveoli).

Summary

Breathing is a mechanical process driven by muscles, regulated by the nervous system, and fine-tuned by chemoreceptors. Its purpose is to ensure continuous gas exchange—oxygen supply for energy and removal of carbon dioxide to maintain acid–base balance.